Native People

Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Lenape people inhabited the Brandywine Valley. Traditional Lenape lands, called the Lenanehoking, extended from the lower Hudson River Valley, down through what is now New Jersey, to eastern Pennsylvania and northern Delaware.

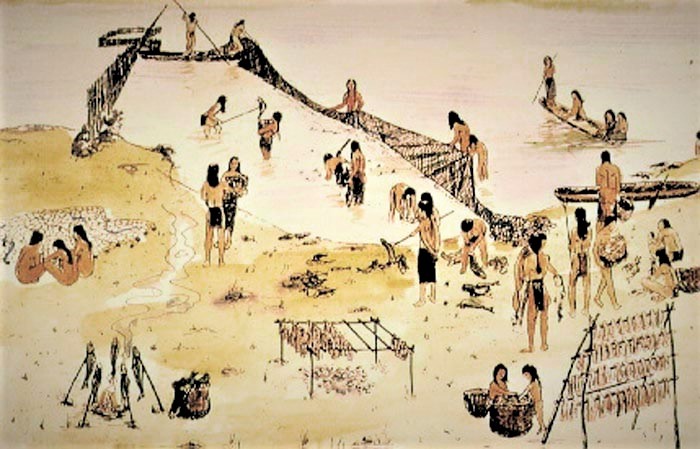

The Lenape cultivated corn and other crops in arable fields, hunted for deer, bear, beaver and caught fish in the creeks and rivers. American shad was without doubt a major food source for the Lenape due to its abundance and migratory behavior which made it easy to catch. During the spring migration they were so plentiful that the river was said to be “boiling” with shad.

Lenape Natives Fishing For Shad On the Brandywine

Native Fish

Traditional Planked Shad Baking

From time immemorial, millions of shad left salty ocean waters each spring to return to the fresh water rivers where they spawned, in order to create a new generation. The mature shad came northward up the Delaware River, and then upstream into one of its many tributaries, the Christina River, and then into two tributaries of the Christina – the Brandywine, in Wilmington, and the White Clay Creek, near Newark.

American shad are quite striking in appearance. Typically 16 to 20 inches long, they weigh 3 to 8 pounds. Their sides and bellies are silver and white, their backs a shiny greenish-blue. Shad were known as “America’s Founding Fish” for a second reason: the run of 1778 arrived at the Schuylkill River just in time to save Washington’s troops from starvation after a long Valley Forge winter.

Conflicting Interests

When colonists built the first dams on the river in the early 1700’s, shad could no longer pass upstream. The Lenape people protested that despite their granted rights to fishing the river, they were being starved. There was a profound cultural repercussion on the Lenape. Samuel Kirk’s 1720 dam set off a decades-long dispute between the European settlers and the area’s Native people.

The shad were the very food that the Lenape depended upon. Kirk’s dam at present day Adams Street in Wilmington stopped the fish’s annual run, thus depriving the Lenape of their historic food source. For these Native people, this was not only a question of catching the fish and preparing them while fresh — the drying of the fish for the Lenapes’ survival over the winter was an ancient, cultural tradition.

The Lenape appealed to the Colonial legislature several times, asking that the increasing number of dams be removed. But the millers’ industry won out over the native inhabitant’s need for food. The dams remained. It was a crushing blow to the Lenape, who felt deceived by what they believed to be an unbreakable treaty they had forged with William Penn in the 1680’s. Even though the Lenape had enjoyed an unusually warm relationship with the colonists since the Swedes’ arrival in 1638, most of the tribe felt it imperative to leave Delaware by the 1750’s — just 30 years after Kirk’s first dam.

Early Industry

With their dam building, colonists were turning the rapid waters of the Brandywine River to profit. The Brandywine’s size and steep drop through the Piedmont offered ideal conditions to power the mills of the early industrial revolution. By the early 1800’s, colonists crowded mills around the Brandywine’s dams and millraces. Along the small section of the river shown in the map, there were over 50 waterwheel mills, powered by five dams. These mills supported manufacture of cotton primarily but also paper, snuff, flour, gunpowder, leather and machinery.

The success of the early Quaker millers was due to the combination of several factors, the most important of which was the Brandywine as a source of water power to turn the millstones which often weighed more than two thousand pounds. The rich soils of Lancaster County Pennsylvania provided an almost never-ending supply of grain. The grain was transported to the mills in specially designed heavy wagons called Conestogas, which were later used to haul goods and families westward across America. The Brandywine estuary near the end of the fall line enabled ships to sail right up to the mills. There the flour could easily be loaded onto low draft boats called shallops, which would then unload the flour onto ocean-going ships.

The Brandywine Today

Today, the great majority of the Brandywine’s dams serve no active purpose.

The State of Delaware has designated the Brandywine as a “Water of Exceptional Recreational or Ecological Significance.” The area possesses a wealth of highly scenic and historic areas. In addition, there are thousands of acres of protected and publicly-accessible land and trails, including several state and city-owned parks. The largest of these public lands is the Brandywine Creek State Park, which contains “one of the most beautiful high canopied woody communities” found anywhere in the eastern United States Piedmont. There are also large blocks of protected private land owned by the Woodlawn Trustees, and other private lands protected through conservation easements held by the Brandywine Conservancy.

Ultimately, to become an American shad sustaining river, passage will need to be created past the ten remaining dams in Delaware. If American shad were able to swim upstream past Dam 11, many thousands of those shad would spawn — providing the foundation for a self-sustaining population.

Recreation at Brandywine Creek State Park in northern Delaware

Restoring shad after an absence of three centuries represents a kind of rebirth of the Brandywine River. A healthy shad population will support many wildlife species, increasing the biological vitality of the watershed. River otter, fox, mink, heron, kingfisher, bald eagle and osprey populations will likely increase with the augmented high protein food supply. In addition to American shad, other migratory fish will also benefit from improving the river’s flow. Restoring these species could create a new type of recreational fishery, and engender fresh excitement in the river.